Several pieces currently on display at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art celebrate the female body. Unlike the filtered photographs we encounter today in magazines and social media posts, these pieces of art capture the feminine mystique through the ages.

From 15th– and 16th-century painted nudes to more contemporary 21st century three-dimensional portrayals—one featuring glitter, beads, sequins, feathers, and symbolic objects—each piece is stunning. “At the Nelson-Atkins, we encourage visitors to see the world from many perspectives,” says Julián Zugazagoitia, director/CEO at the museum. “By viewing the Renaissance works in the original Nelson-Atkins building, then contrasting those with contemporary works in the Bloch building, our visitors can consider the evolving view of the human body, as well as join the critical dialogue surrounding race and representation in the world of Western art history.”

Here are five can’t-miss pieces you need to appreciate up close and personal:

5) Celestial Woman Undressed by a Monkey, Madya Pradesh, ca. 975–1000

“This Indian sculpture of a Surasundari, or ‘beautiful celestial goddess’ is depicted partially nude. Her state of undress helps to tell a story. As she stands grasping the edges of her garments, she looks down to see a playful monkey pulling her lower garment down, revealing her buttocks. This would have been a humorous scene for its original audience. We also know that this figure was intended to be beautiful by its own cultural standards.

The ancient Indian text on temple building, the Shilpa-Prakasha, states that the upper levels of the temple should be filled with images of beautiful celestial goddesses and male and female couples. Their presence would bestow blessings and protection on the temple.” — Kimberly Masteller, associate curator, South and Southeast Asian Art

4) Nemesis, Albrecht Dürer, ca. 1501–1502

“Albrecht Dürer’s winged Nemesis, the Greek goddess of divine retribution, floats in a heavenly void above a panoramic view of a mountain village. Prepared to pass judgement on the inhabitants below, she holds a bridle to punish the arrogant and a lidded goblet to reward the deserving.

Her imposing figure, emphasized by the stark white background, loosely follows the rules of proportion developed by ancient Roman architect Vitruvius. Depicting the human form according to system of mathematic measurements was a central preoccupation for Dürer throughout his lifetime.” — Rima Girnius, associate curator, European arts

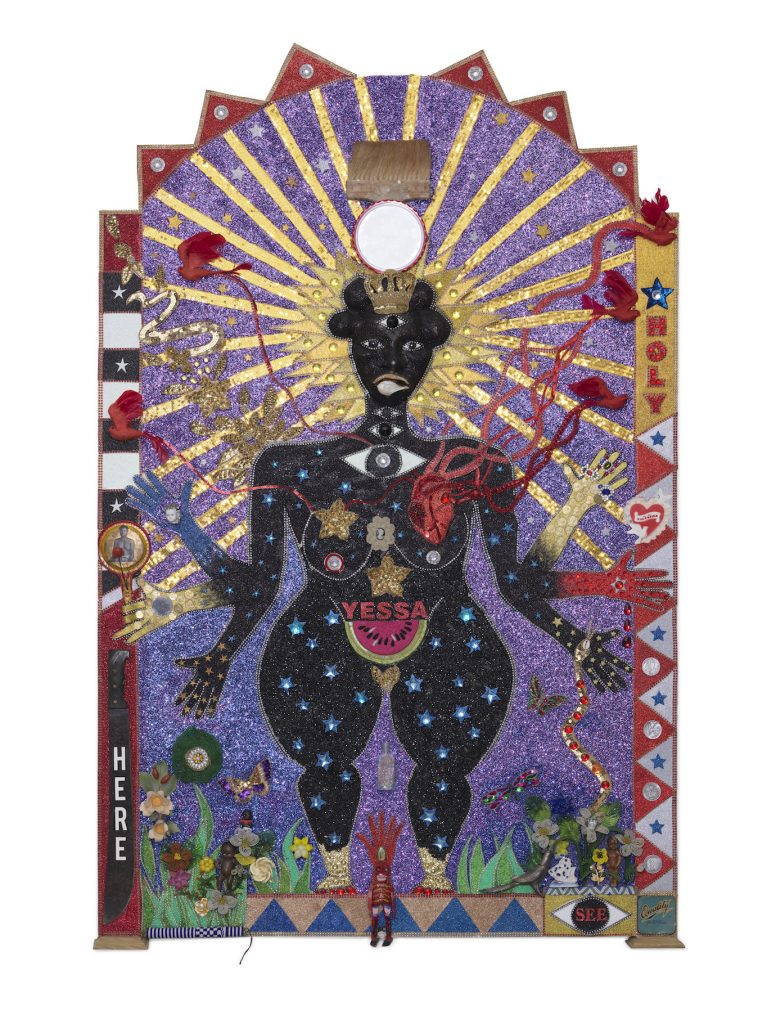

3) Glory, Vanessa German, 2017

“Based on the loa or spirit figures adorning a vodou flag, Vanessa German’s Glory creates a symbolic body that stands in for the Black woman in America today. Her dynamic mixture of found materials referencing the slave trade, ethnography, religion, pop culture, consumer culture, and communal experiences, all in a dazzling collage held together by spirit and by glitter. German’s powerful frontal figure is both individual and collective, making us realize how the body is many things all at once.” — William Rudolph, deputy director, curatorial affairs

2) The Three Graces, Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1535

“Lucas Cranach the Elder depicts The Three Graces, daughters of Greek god Zeus, on a narrow stone ledge against a dark undefined background. Robbed of narrative detail, the focus rests entirely on the stylized beauty of the nudes and the artist’s skill in rendering them. Each figure adopts a pose that shows off a different side of the body, demonstrating the artist’s mastery of three-dimensional form. The diaphanous veil that snakes around their bodies unifies the sisters but does little to conceal their nudity.” —Girnius

1) Figure with Skirt, Simon Leigh, 2018

“Simone Leigh, who will represent the US at the 2022 Venice Biennale, celebrates the Black female body as ‘a repository of lived experience.’ Our sculpture blurs the lines between figural representation and architecture. On top of this towering figure’s head is a vessel symbolic of feminine strength and accomplishments, including childbirth and healing.

Clothed in a bell-shaped gown of raffia grass, a material often used in traditional African architecture, the body becomes architecture, suggesting women as makers of home, culture, and community. The mixture of textures and materials also provides visual excitement.” — Rudolph