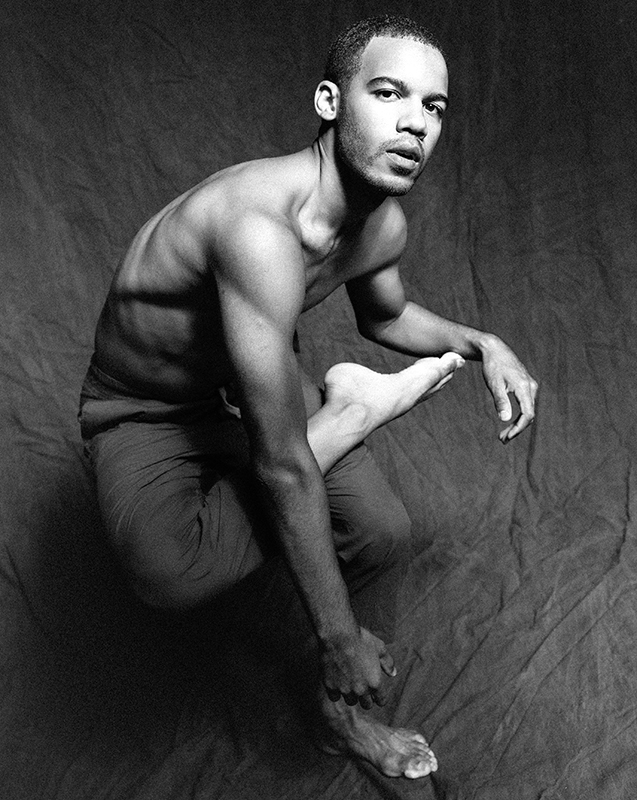

Growing up a shy kid in a South Kansas City neighborhood with a rich mix of ethnicities, Tristian Griffin learned that when language was a barrier, he could communicate through “movement language.” Today the celebrated dancer and choreographer behind Tristian Griffin Dance Company takes movement language to new heights, creating and performing works across the country.

Griffin didn’t take up dance until age 11, but by freshman year at St. Thomas Aquinas High School in Overland Park, his talent was obvious to dance teachers. A summer dance intensive at Virginia School of Arts led to a full year at boarding school there, with coursework in the mornings and studio work late into the night.

After graduating from Raymore-Peculiar High School, Griffin earned a BFA in ballet from Texas Christian University and began his professional career at Garth Fagan Dance Company in Rochester, New York, where he performed at Lincoln Center. He has danced as a guest artist with companies around the country, including Metropolitan Opera and Lyric Opera of Kansas City. More than 15 professional companies and arts organizations have commissioned works by him. His full credits are at tristiangriffin.com and he posts videos and photos of his choreography on Instagram, @tristian_griffin.

Griffin is currently choreographing in Newport, Rhode Island, and San Diego. He also teaches at University of Kansas. He spoke with IN Kansas City by phone recently from Denver, where he was working with one of his dancers on a commission for Johns Hopkins in Baltimore.

What is your earliest memory of dance?

I asked my mom, “Did I dance ever as a little kid?” and she was like, “No. All you said was that one day you would change the world. You kept saying that, but you never showed any interest in anything in particular besides Power Rangers.”

I started dancing with my brother when I was 11 or 12. He was 8 or 9. We were blessed with good genes. We have photogenic faces. So we did modeling, and we were advised by our modeling agency to pick up talents because it’s not enough to be just a model. So we took singing lessons and dance lessons.

Singing didn’t work out. [Laughs] Dance for some reason—I just felt a pull toward it.

What was the pull?

I was able to express myself without having to use words, because I really don’t like speaking, especially public speaking. But I can display what I mean through movement. I can do that all day long.

It didn’t come fully into focus until I met this wonderful woman, Michelle Hamlet-Weith, who is still my mentor to this day. She recruited me to come to her dance school my freshman year at St. Thomas Aquinas.

She said, “You’re very talented. You need to drop everything and dedicate your life to this. If you want to do that, I will train you.” I played football at Aquinas, I played basketball. I’m a nerd, especially when it comes to history and science, so I was taking AP courses. I ended up having to dial back a lot to spend more hours in the studio versus in the library and on the field.

That’s when I started this journey and really dedicated my life to dance.

Kansas City has a lot of high-profile dance companies. Where do you situate Tristian Griffin Dance Company in the Kansas City dance scene?

Unfortunately, I feel like the Kansas City dance community has pulled themselves into different regions.

What do you mean by that?

I feel that most dance companies in Kansas City understand their voice and the client and they stick with that. They don’t intersect with other companies or communities to expand their audience or their impact.

Tristian Griffin Dance Company tries to push the envelope by collaborating with people like [artist] José Faus, [poet] Glenn North, [musician] Calvin Arsenia, [artist] Debbie Barrett-Jones. These people represent different art forms and different communities.

I’ve done a program called Palimpsest through Charlotte Street Foundation, the Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, as well as Lawrence Arts Center. I’ve done three renditions where I’ve pulled in six to seven featured collaborating artists. It’s a smorgasbord of communities and cultures intersecting. I want the audience to come to TGDC expecting to be transformed through hearing stories that are outside their world.

‘‘I’m interested in elevating minority or marginalized stories to be heard and seen. And also, I just want high-caliber art. I want to show the best of my ability, my dancers’ abilities, and my collaborating artists’ abilities. I won’t sacrifice the quality for the sake of collaborating or for the sake of being in an avant-garde space.”

What themes spark your creativity?

I’m interested in elevating minority or marginalized stories to be heard and seen. And also, I just want high-caliber art. I want to show the best of my ability, my dancers’ abilities, and my collaborating artists’ abilities. I won’t sacrifice the quality for the sake of collaborating or for the sake of being in an avant-garde space.

As a Black choreographer, do you feel pressure to conform to other people’s expectations of Black traditions in dance?

Oh, gosh, yeah. What is Black dance? That is a stigmatizing label that is thrown onto people who venture outside of Black dance companies. Dancers working with a ballet company or a contemporary company might even be asked, “Why aren’t you pursuing Black dance?” And when you choreograph a work and it doesn’t have the themes of Black dance, they ask, “Why aren’t you choreographing Black dance?” So you get boxed in.

What do people mean when they say Black dance?

It’s a precondition. It’s expectations. It’s assumptions. If you really want to dissect it, Black dance has foundation pillars. When someone asks, “Are you a Black dance choreographer?” they are looking for those themes in the work.

An interviewer told Bill T. Jones that he was one of the most successful Black choreographers, and he said, “Whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa. I’m not just a Black choreographer. I am Black and I do choreograph, but don’t limit my art to my race or ethnicity. It transcends that.”

I feel the same way. I am not saying I’m disclaiming or trying not to be a part of the African-American community. I am saying that our success should not be limited based upon our race, based upon our culture. It’s a beautiful thing to say I’m the first Black person to do da-da-da, but what if I’m the first person generally to do da-da-da? That to me holds more power. If someone is the first at something or the best at something in general, I don’t see the significance of adding “Black” in there.”

It almost diminishes it.

Yeah. You don’t hear people saying “the first white person” to do something. It just sounds weird. So why is that accepted for Black people?

When you talk about the foundational pillars of Black dance, are they thematic or movement-based?

I would say thematic, which ultimately leads you to movement that streams into the works that are called quote-unquote Black dance.

What’s an example of that?

Oh, you’re getting me into hot water. I think the number one thing you see in Black dance is struggle. I can confidently say that from my experience and conversations, but there’s not a book out there called “Black Dance” that you can read.

You often cast dancers who do not have the so-called “ideal ballet body type.” Is that becoming more widely accepted or do you feel it is still a struggle?

It’s still a constant struggle unfortunately. It’s really a barrier that exists in all forms of dance but particularly in ballet. I don’t cast people because, “Oh, this will be great—they don’t have the ballet body.” No.

I want to see three things in a dancer: One, do they bring the movement across on the stage, like break the fourth wall? Are they willing to work with me and the other company members, are they collaborative? And then, are they going to represent TGDC outside the studio? I believe in branding and not just a dancer existing in the studio. If a dancer is doing something crazy outside the studio, that reflects poorly on me. If they are teaching and they decide not to show up for work, that ultimately gets back to TGDC.

You wear two hats. You’re a choreographer but you still dance. How do you balance the two?

I am old bones. Dancers age like dogs. We age about five years a year. Our bodies dwindle very significantly. So I’m kind of towards the end of my dance career. Now I’ve made it a mission to only accept roles that fulfill me. Before I just did things because it was a paycheck or an opportunity.

As a shy person, what motivates you to get up on a stage in front of people?

I’m able to transform. It’s like Kansas City Ballet’s Jekyll and Hyde, where two people exist inside one body. I’m shy but when I go onstage, I can transform into this other person who is demanding of their space and does not shy away from hundreds of people looking at them. I actually use that as fuel.

You’ve had the opportunity to travel widely. What keeps you in Kansas City as a home base?

Kansas City’s home. Most of my family is in Kansas City, and I am very close to my family. But I find myself needing a beacon, a place I can always feel at home. And Kansas City is very easy to get to and leave from. Versus being bicoastal, which is greater distances and higher costs of living.

What creative ideas are rolling around in your head for future works?

I just did a residency at Jacob’s Pillow in Becket, Massachusetts, where I was able to create a duet from scratch. You have two mentors who advise you throughout the residency, so I was really able to refine my idea. The duet talks about the themes of identity, masculinity, and delicateness between males, specifically Black and Brown males. Those cultures put up barriers so that your true identity is not able to surface. I want to showcase the duet in Kansas City.

Thinking back to telling your mom you were going to change the world, what is the change you would most like to bring about?

Making space for liberation. I don’t have to fight the fight to liberate people, but I think creating work that creates the space for people to talk about dismantling and reconstructing and healing.

Interview condensed and minimally edited for clarity.