It’s a sight you might not expect to see in Overland Park.

A long line of vehicles curls around the parking lot of New Haven Seventh Day Adventist Church at 87th Street and Antioch Road. People are there for the Renewed Hope Food Pantry (RHFP) that church members started in 2011. From quietly helping a few people who needed food, the pantry’s outreach has grown to 91,436 visits from 25,687 households in 2023. On Tuesday mornings as well as afternoons on the first and third Sundays of the month, they come for a sack of potatoes, frozen meat, day-old bread, and canned goods.

“People’s struggles are hidden, but real,” says Karen Whitson, director of RHFP. “Many people are working, but not making ends meet. Or they might have a crisis. A couple who lost their jobs, someone else who had medical bills to pay off.”

Fixed expenses like mortgages, rent, car, and cell phone payments often come first. Food can flex. It can be last, and that can mean food insecurity.

The USDA defines food insecurity as a lack of consistent access to enough food for every person in the household to live an active, healthy life.

Food pantries like RHFP, the Jewish Community Center, Catholic Charities, and Nourish KC rescue day-old baked goods and other food items from local groceries like Hy-Vee, Price Chopper, Sprouts, Whole Foods, and Target, organize the donations, keep records, and work the pantry, “It takes a lot of people and work and time to get the food to where it is needed,” Whitson says. RHFP’s Hope Bus mobile pantry goes out to “food deserts” in the metro area, places where fresh food is not readily available. “When our bus shows up, people’s eyes light up,” Whitson says. And for her, it’s about more than hunger. “When you remove food anxiety, there can be peace in someone’s home.”

Hunger and Health

Food insecurity seems to make no sense in a land of plenty. It’s a complex, knotty problem that Kansas City nonprofits are trying to untangle, each in their own way.

“America grows over 2½ times the amount of food it would take to end world hunger,” claims Michael Watson, former UMKC and Boston Celtics basketball player and current executive director of the nonprofit After the Harvest, part of a national network. “Food waste is one of the problems,” he maintains. “So much of farm produce is Grade B and not aesthetically pleasing enough to sell in grocery stores. A Grade B potato might be misshapen, an apple a little too small. They’re still edible and nutritious, but not perfect.” If farmers have nowhere to send Grade B produce, it ends up in a landfill. According to the USDA, food loss and food waste are two of the leading causes of greenhouse gases, so there is a climate impact.

After the Harvest works with farmers to send teams of volunteer ‘gleaners’ to pick the imperfect produce to redistribute through Kanbe’s Markets, Harvesters, and local food pantries.

Watson is championing a new program called Urban Produce Push or UPP, which he hopes will go nationwide. UPP identifies ten zip codes in the metro area with high food insecurity and encourages local businesses and individuals to “adopt” a zip code and provide fresh produce to those areas. “Much of the food you find in food deserts is sodium-packed,” he says—think of the highly processed convenience foods stocked at mini-marts and gas stations—and can lead to health problems such as high blood pressure. Greater availability of fresh fruits and vegetables can help moderate those problems.

Growing your own food, even in urban areas, can also help fight food insecurity while promoting better health. “While gardens are not the first response when we tackle food insecurity, we can address nutrition insecurity,” says Jennifer Meyer, executive director of Kansas City Community Gardens (KCCG). “In urban areas, an apple costs as much as a package of ramen noodles. If you’re hungry, you probably reach for the ramen. That’s why obesity runs parallel to food insecurity.”

Since becoming a nonprofit in 1985, KCCG has been helping low-income families save money on grocery bills. “We are seeing an incredible rise in people growing their own food since the 2008 recession and more recently, the pandemic,” she says. “Somehow, we lost a generation of gardeners. Now people aren’t quite sure how to do it. We work with anyone in the metro area who wants to grow food for themselves or to share with others,” says Meyer. KCCG’s Beanstalk Garden helps educate kids about fresh garden food.

Who Is Food Insecure?

According to Harvesters, in the metro area:

- 35% are children

- 15% are seniors

- 61% have at least one adult in the household who has worked in the last year

- 9% are living in temporary housing or are unhoused

- 57% are white, 16% are Black, 20% are Hispanic, and the rest are from other racial and ethnic groups

Hunger and Children

It’s not only fresh produce, but also protein that can be lacking in the diets of the food insecure. When working moms pick up their kids from Operation Breakthrough (OB), they also can take a protein-packed nutritious meal home with them, courtesy of the new nonprofit Pete’s Garden. After watching Anthony Bourdain’s documentary Wasted, Tamara Weber was shocked at the scope of food waste and wanted to do something about it. “Kanbe’s Markets were just starting, I volunteered to glean with After the Harvest, but I’ve always been interested in start-ups and I wanted to do more,” she says. “The piece that was missing was prepared food. I wanted to reduce food waste while making it easier for parents to have a healthy meal with their kids.”

After talking with Mary Esselman, OB’s president and CEO, Weber designed a pilot program in 2019. Weber organized prepared food-service donors, such as American Century’s onsite employee cafeteria, local caterers, and restaurants. She picked up the food in her SUV, drove it to OB’s commercial kitchen, and repackaged it (following all food safety protocols) for moms to take home. It was a success, and Pete’s Garden became a nonprofit the next year. Today, they work out of the commercial kitchen at Grace & Holy Trinity Cathedral. In 2023, Pete’s Garden provided 100,000 packaged meals through even more partners, including Jewish Family Services, Boys and Girls Club, Avenue of Life, and St. Paul’s Episcopal Church.

What a Difference Five Miles Makes

Johnson County is the wealthiest county in the state of Kansas. And yet, one in seven residents can be classified as low income (meaning they live on less than $46,060 for a family of three). Low income can result in food insecurity, poorer health outcomes, and lower life expectancy.

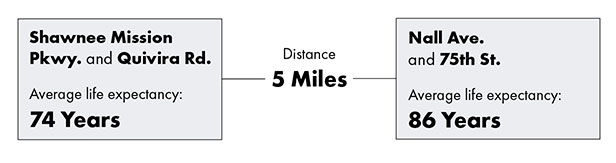

According to the Community Health Assessment report compiled by the Johnson County Department of Health and Environment, here is the health difference between a lower and a higher income area:

Hunger, Homelessness, and Hope

People who line up at Renewed Hope Food Pantry still have their vehicles, their homes. Operation Breakthrough moms have jobs and a place to live. The most food insecure of all are the ones who have none of those, says Ross Dessert, president of the all-volunteer Uplift Organization Inc.

Since 1990, Uplift has been bringing a hot meal and basic essentials (toiletries, socks, underwear) to several hundred homeless in five to ten locations and encampments around the metro area, three times a week. Like the Pete’s Garden food-rescue model, Uplift uses a commercial kitchen and partners with restaurants like Garozzo’s and catering companies to repackage food that is then served from their vans.

“The numbers of homeless have increased since the pandemic,” Dessert says, “and we also notice an uptick in young homeless in late spring and early summer, when they have aged out of the foster care system and are no longer in school. The new 18-year-olds out on the street are hard to see,” he admits. “When I first started with Uplift, I saw people in need, but not the kind of desperation we see now,” in part due to the lack of affordable housing, Dessert says.

“Uplift doesn’t solve the problem,” Dessert admits. “What we’re doing is not just the food, it’s also showing care and compassion from the community. It’s not just about feeding the body; it’s about keeping the spirits up. If you have hope, you can make the change you need to make in your life.”

Feeding the homeless “changed my heart,” he says. “It makes you see things in a different way. There’s a ripple effect.”

And the ripple reaches us all.