In photographs, the most famous muckraker of Mission Hills, Thomas Frank, is always smiling, even when it looks like he’s trying not to. On the phone, his rising inflection and buoyant laugh leave the impression that humor is a life ring that keeps him from sinking into pessimism about the sorry state of American politics he has borne witness to his whole career.

After graduating from Shawnee Mission East in 1983, Frank attended University of Kansas for one year before transferring to University of Virginia where he earned a degree in history in 1987. He earned a Master’s and PhD at University of Chicago, specializing in 20th-century American cultural and intellectual history.

He founded The Baffler, a leftist journal, in college, drawing the original logo on a drafting table in his dad’s office in midtown Kansas City in 1988.

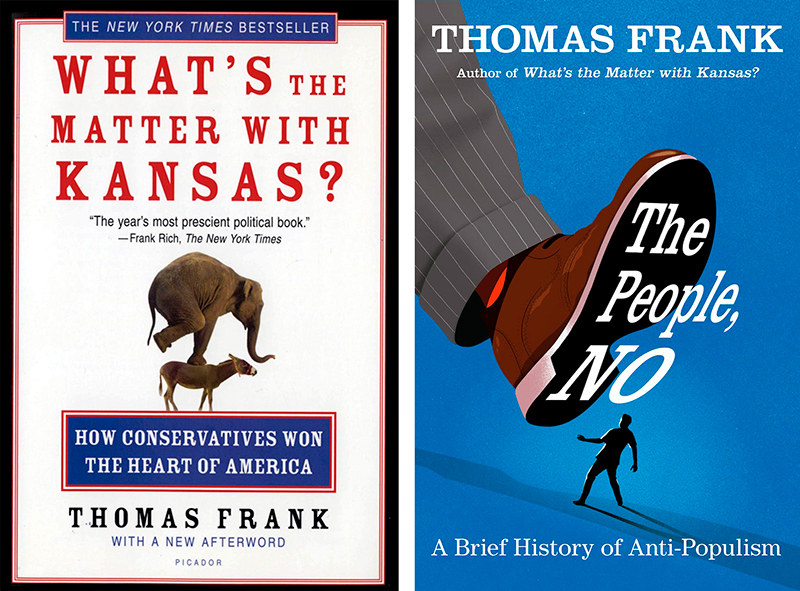

In 2004, Frank achieved national fame and became a darling of liberals when he wrote What’s the Matter with Kansas? / How Conservatives Won the Heart of America. From 2008 to 2010 he wrote a left-leaning column in the Wall Street Journal. He is also the author of Listen Liberal / Whatever Happened to the Party of the People (2016), a book that earned more controversy than praise among liberals, and The People, No! / A Brief History of Anti-Populism (2020). Frank has also written for The Guardian and Le Monde Diplomatique but is currently focused on a new book project.

In a lengthy phone call from the home he shares with his wife and two children in Bethesda, Maryland, Frank reflected on the repercussions of Roe being overturned, how his most popular books have withstood the passage of time, and why he feels the time has come for him to walk away from politics.

In What’s the Matter with Kansas?, you argued that conservatives use culture-war issues, including anti-abortion rhetoric, to get voters on board, but in office, they focus instead on economic policies that gut the working class. You theorized that conservatives weren’t serious about overturning Roe v. Wade.

Yes, isn’t that funny? That’s totally what I thought back then. And I still think that was a correct analysis of where we were at the time.

When Roe was overturned in June, one columnist wrote that she hoped you apologized to the women of Kansas, because the fears you dismissed had come to pass.

Yeah, there’s a lot of bad faith there. We’re awash in bad-faith arguments today, so that’s not saying much.

What’s the Matter with Kansas? came out in 2004, and I was describing the immediate past, the ’80s and the ’90s. The country was caught up in all these culture wars, and they were successful for building the right-wing movement, but they were not very successful at changing the direction of the culture. And that was not a unique position held by me, a lot of people were saying that.

The great example of that was Ronald Reagan. Rhetorically he embraced the pro-life movement but clearly, he didn’t believe in it. When he was governor in California, before Roe v. Wade, he signed into law the measure that legalized abortion in California. Whenever he talked to the anti-abortion people, he would not show up in person, he would do it by telephone. He always kept them at arm’s length. Conservatives used to complain bitterly that they could not make headway, that the culture would barrel on out of control. And that was true.

The same was true of George W. Bush. He mobilized the culture wars to get elected and then didn’t care about them once he was in office. Both those Republican presidents were only interested in economic policies. Ronald Reagan completely changed the face of this country through deregulation, tax cuts, and freeing up the banking industry. But he didn’t change the culture.

In What’s the Matter with Kansas? you described the bait-and-switch that conservative leaders con voters with: “Vote to stop abortion; receive a rollback in capital gains taxes…Vote to screw those politically correct college professors; receive electricity deregulation.”

Right, and [Reagan and Bush] named lots of people to the Supreme Court, but they somehow never did anything about [Roe v. Wade].

What changed?

In a word, Trump. Here comes this guy that I think of as a moral Caligula. He embodies the hypocrisy of these politicians who clearly don’t believe what they are saying in terms of morality and family values, and he takes it to an extreme degree: He’s on wife number three, he dated a porn star, the remark that got caught on a hot mic—this is not a man that respects family values.

But I’ll be damned, he appoints three justices to the Supreme Court and they actually overturn Roe v. Wade.

Why do you think that happened?

There’s a very good reason Republicans don’t try to win the culture wars. It’s because they know their position is a losing one. The abortion issue mobilizes one group of people but it’s a loser in the broad scope of things. Polls consistently show Americans favor abortion 70 to 30 [percent], and it might be closer to 80-20 if you phrase it the right way.

Look at Kansas: This is a state that elected Sam Brownback, the most publicly pious culture warrior of our time, but at the same time, the right to an abortion is generally popular. So, the Right had to walk this fine line for decades.

But Donald Trump didn’t get the memo. [Laughs] He didn’t understand this at all. He just goes out and does this and now, you watch: This is not going to turn out well for Republicans. They are going to reap the whirlwind.

Kansas women showed they are not to be messed with, for sure. The right to abortion passed by an 18-point margin. No one should have been surprised: In What’s the Matter with Kansas?, you documented the state’s history of progressive ideas and strong women leaders.

Yes, that’s an aspect of Kansas’s history that does not get enough attention. It’s not like these are right-wingers and they’ve always been right-wingers. The populist movement has always fascinated me and one of the most interesting aspects of it was that—uniquely among major political parties of the day—it had strong women leaders.

And Kansas also, weirdly enough, had been one of the states to liberalize its abortion laws before Roe v. Wade. Only about 12 states did this.

William Allen White once said, “Everything happens in Kansas first.” Kansas was the first state to vote on abortion rights after Roe was overturned. Now California, Vermont, Kentucky, and possibly Michigan, will have abortion rights on the ballot in November and more states are trying to get a vote in the coming two years.

Yes. If the Democrats are smart, they’ll get abortion referendums on the ballot everywhere in America. Just like back in 2004 when Karl Rove contrived to get referendums on gay marriage on the ballot in states to increase conservative voter turnout.

So the result of Roe being overturned might be that abortion rights will be better protected, rather than always hanging under the threat of a Supreme Court ruling.

Yes. Ruth Bader Ginsberg always said having abortion rights only by decree of the Supreme Court opens you up to all sorts of criticism, when it should only be about women’s rights to control their own bodies, and it should be done in a direct way that can’t be overturned, and the way you do that is by law.

In Listen, Liberal, which came out just before the election in 2016, you argued that the Democratic Party abandoned blue collar workers in favor of professional elites. You warned that assuming voters would continue to rally to Democrats simply because they were not Republicans was not going to work. The book got very little coverage when it came out, but after Trump won, it got a lot of attention.

Yeah, it was kind of too late then, right? When the book came out it was very controversial, but now that analysis of the Democrats is all over the place.

Does that make you feel vindicated or frustrated?

Listen, the story of my life is the great turn to the right in the late ’70s and early ’80s. I mean, we changed the way this country worked. And we did it in a way that has been disastrous for ordinary Americans. And we’ve never even come close to putting that up for debate as a country. Like saying: Maybe we shouldn’t have done that. Maybe we should have followed a different path. There are people out there who are saying we need to reexamine the entire direction that we are going—mainly people like Bernie Sanders—but the Democratic Party is determined to not listen to them.

I have a French friend who has been coming over once every four years since the ’90s for our political conventions. He says, “Every four years I come over here, and it’s a little bit worse.” And he’s right. Every four years, people have sunk a little more into despair.

One of the parts of What’s the Matter with Kansas? that still gets me is my description of the crumbling small towns. And that’s just gotten worse.

If you live in Kansas City and you work in the information industry or you’re a member of the professional class or you do some kind of creative work, things are great. Kansas City’s a really nice place to live. If you live almost anywhere else in the surrounding states, your way of life is crumbling. That really bothers me. In all my years covering politics, I haven’t seen anyone even try to come up with an answer for that.

In The People, No! you write that Clinton, Obama, and Trump were all phony populists. Do you think it is possible for a real populism to take root today?

Absolutely. My sort of grand vision of American politics is: We’ve got this political system where something is missing. There’s a hole in it. That thing that’s missing—and it’s been missing my entire life—is the traditional labor left.

That is what populism meant, was doing that kind of traditional left-wing politics. There is nobody occupying that space. What you have instead is all these fake Lefts cropping up. Not necessarily political, but advertising, foundations, people claiming to be radicals. People talking about liberation, how products “liberate” you. There are hundreds of examples. Trump is a fake leftist, by the way.

How so?

He speaks this language of liberation and empowerment and doesn’t mean anything by it. Clinton and Obama did the same thing, in a different way of course. We are awash in fake populism. Now, I’m using the word in its original meaning, which was a trans-racial working-class movement for economic democracy.

You point out in your book that the word “populism” was invented in Kansas.

Yes, isn’t that interesting? I was able to track down within a week when the word was invented and the first use of it in print, in a newspaper in Winfield, Kansas [on May 28, 1891]. The book then traces how the word changed over the years and was used to describe all kinds of crazy things.

Now Trump and the Republicans are saying they are going to make the Republican Party a workers’ party. This is absolute nonsense. But they are succeeding. It’s What’s the Matter with Kansas? 20 years later—the strategy is still going.

In light of all the fakery, why do you think a real populism can take hold?

It’s because there are all these fake versions. That indicates to me some kind of longing for the real thing. That’s what all my books have been about. Before What’s the Matter With Kansas?, I wrote One Market Under God, which was about one of these fake Lefts—the bull-market culture of the 1990s and the insane dot-com bubble, where every company and every stock and every investment strategy was sold to the public as a form of economic liberation. They called it the New Economy, and it was going to overthrow old economic hierarchies. That turned out to be complete bullshit.

And the internet was going to be a great democratic leveler because everyone was going to be allowed to say whatever they wanted with no gatekeepers.

That’s perfect. Yeah, that’s another fake populism that doesn’t come true. Instead, the internet has turned into an enormous surveillance machine. It’s ironic that it was sold to us as a device of liberation.

Are there any political developments that give you hope that workers have a chance?

Oh, sure. There are all kinds of hopeful things. There seems to be a mini-boom in people organizing their workplace. That is great to see. I’m very happy about that.

And you know, Biden—I wasn’t a big fan for most of his career. But I think he’s done a lot of bold things. For example, pulling out of Afghanistan. I think that took guts, and I’m glad that he did it. And Barack Obama was such a deficit hawk and believed in austerity. Biden hasn’t shown any signs of that. I think his move on student loans—I’ve got issues with it here and there—but at least he is starting to do something about the problem.

“I’ve written critiques of both parties, how they operate, who they answer to. I’ve pointed out the way both of them dance around the all-important subject of social class, refusing to address it directly.”

What are you working on now?

I’m trying to get away from political writing, trying to get back to what I wrote about years ago.

Which is what?

Cultural history. I think the time has come to walk away from political stuff.

Why?

Because I’ve said what I wanted to say. I’ve written critiques of both parties, how they operate, who they answer to. I’ve pointed out the way both of them dance around the all-important subject of social class, refusing to address it directly. And as our politics descend ever deeper into culture-war pathology, I feel like I would just be saying the same things over and over. Time to move on to other aspects of life.

Even though you’ve been gone a long time, do you still feel a connection to Kansas City?

Yes. The city made me, and it is the only place in the world where I am organically adjusted to the rhythms of life.

Interview condensed and minimally edited for clarity.