One of the top experts on America’s grandest European Revival-style houses—from the Elms in Newport to Cheekwood in Nashville to Andrew Carnegie’s Fifth Avenue mansion (now Neue Galerie New York)—was raised in Roeland Park. Independent scholar Michael C. Kathrens attended Shawnee Mission North High School and University of Missouri-Kansas City. He has always loved research, but academia did not suit him. He lived in New York for 23 years, then spent three years in Newport before returning to Kansas City ten years ago.

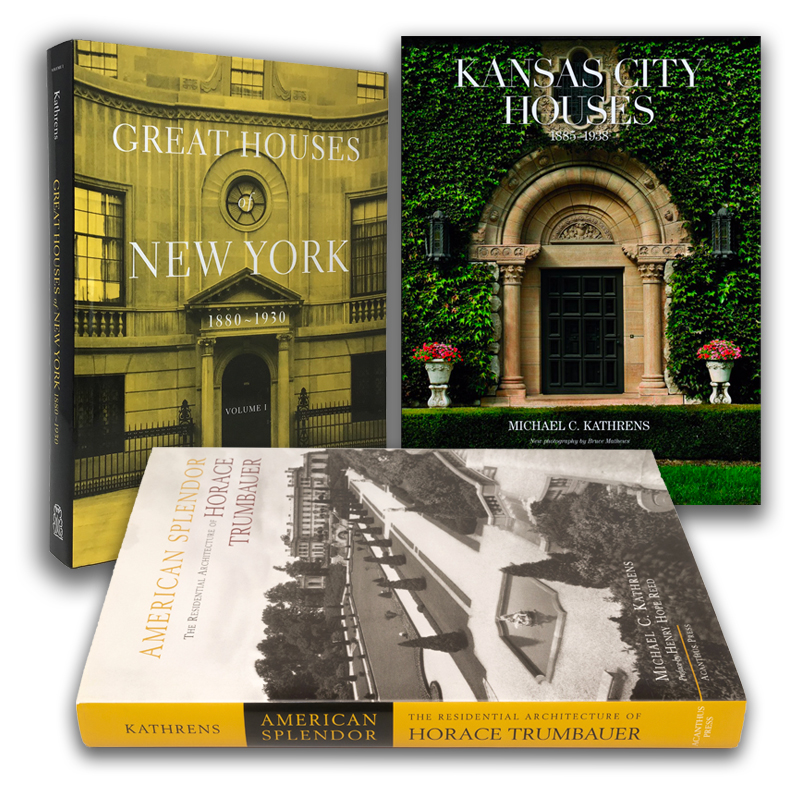

Kathrens published his first book, American Splendor: The Residential Architecture of Horace Trumbauer, in 2002. The book sold out and had several printings, as did his subsequent works: Great Houses of New York, 1880-1930; Newport Villas: The Revival Styles 1885-1935; Great Houses of New York Vol. 2 1880-1940; and Kansas City Houses 1885-1938. His newest book, Newport Cottages 1835-1890, comes out April 3.

Kansas City Houses is in its third printing and will be available in March or April at Rainy Days Books, Stuff, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, The Little Flower Shop, and Pryde’s.

Kathrens spoke at length by phone with IN Kansas City about our city’s finest homes and how their stories reveal the history of Kansas City’s boom period.

What sparked your passion for residential architecture?

My father was interested in residential architecture as a hobby, so that gave me an entrée. And then when I was 12, I found a book called Great American Mansions and Their Stories by Merrill Folsom. In that, I particularly became enamored of European Revival-style houses in America in the period of 1880 up to about 1930.

I remember reading about the Breakers and Ochre Court in Newport, and the Elms—and that was when I fell in love with Horace Trumbauer’s work. He did the Elms, a French Classical-style house in Newport, and it’s just done beautifully. I appreciated him for the thing he was criticized for: People said he stayed too close to 18th-century proportion. My feeling is, if you’re doing a Revival style, you need to stick to the proportions for it to be correct.

What do you love about doing historical research?

You go in and look at things that nobody has looked at in 50, 60, 100 years—it’s new information that isn’t published. And you see patterns and develop theories, and then when you discover your theories were correct, how exciting is that?

How did you get your first book published without having any academic credentials?

Acanthus Press in New York was founded by Barry Cenower. He had an architectural and decorative arts bookstore that mostly sold rare and out-of-print books. I got to know him because I bought books from him. When the margins were no longer there for selling those books, because people didn’t know what they were and would put them on eBay for ten bucks, he decided to do new works. He knew I had a passion for Trumbauer and said, “Why don’t we do a book?”

So, getting my first book published was easy. Normally it’s very difficult. And once you publish one book, it’s easier to get the next ones published.

What qualities make a house great, regardless of its style?

Quality, proportion, and scale. Sometimes people want to try something new, but that doesn’t always work. If the proportions don’t work, you end up with a hodgepodge, and you can see that today in some very expensive homes.

Are there differences in Kansas City’s European Revival-style houses compared to those in New York and Newport?

The houses in New York City and Newport are much grander than the Kansas City houses. Kansas City, even in the era when they were building the really fine houses, was always a conservative town. The owners didn’t want to spend the money, particularly for the interior fine paneling and marble floors—you have a little bit of that in Kansas City but not a lot. But there is a quality that is consistent.

Some people don’t realize that Kansas City was a boomtown from the 1880s to about the 1930s, and there were huge fortunes made because of the manufacturing here and wheat and cattle. The one I was shocked to learn about was oil. There weren’t oil fields around Kansas City, but many people from Texas and Oklahoma (with oil wealth) moved to Kansas City because it was the financial juggernaut.

The homes in your book are presented in order by the year they were built, and it’s fascinating to see the interiors evolve over time. Can you describe the shift that occurs from 1885 to 1938?

In the 1880s, they were what we would call Victorian, with heavier detailing and bric-a-brac. Then in the 1890s, there’s a Classical Revival with rich ornamentation, marble floors, wrought-iron balustrades and ornate paneling, all sourced from Europe.

In the ’20s come the Tudors and the Georgians that Kansas City is known for. Georgians would have been traditional red brick with classical detailing outside and inside, there’s plasterwork and it’s lighter.

But the Tudors are what we are best known for. One of my favorite Tudors is the Penrod House at W. 55th and Summit streets. Its interiors were very East Coast. Very formal entrance hall. The house was built by John Penrod, president of Penrod Walnut and Veneer Company. He had a daughter named Blanche who married Ralph Jurden, who was also in the wood industry in Memphis. When Penrod and his wife died a few years later, Ralph and Blanche moved back to Kansas City and took over her parents’ house. They added on to it and created what we see today. It has very elaborate interiors and exteriors. It’s one of the finest European Revival interiors in the city. It reflects what you’d see on the East Coast, which is not surprising, because the Jurdens summered in the Hamptons, and he was a big polo player, so they hobnobbed with all those East Coast socialites.

I cannot prove the architect who did the additions on it, but I think it was an architect who worked on their house in Memphis, Bryant Fleming. Fleming designed Cheekwood in Nashville, which is very elaborate inside.

The building permit was signed by Ralph Jurden rather than an architect or even a contractor. I found out from a society article that [Fleming] was in town at the time [the Jurdens] were doing the work on the house. Fleming did not have a license to practice in Missouri. So that’s my theory about why Ralph Jurden signed his own building permit.

Where in Kansas City do you live?

In the Valentine/Roanoke neighborhood. I moved back to Kansas City about ten years ago and it was going to be temporary. I had moved to Newport and did writing there for three years, but it was a bad economy, and I couldn’t find a job that paid anything. So I thought I’d just move back here for a while.

I got a job as a designer at Mitchell Gold + Bob Williams in Leawood. But then I had a major stroke eight years ago. It’s good I was here, with a good job and good benefits and family to look after me. It was difficult for a year or so. But I was lucky. They have really good drugs now if you get them within two or three hours. I was mostly recovered after three months, and I’m about 95 percent now, just a few minor issues that I can certainly live with.

What is your home like?

I live in a little 1920s apartment complex. By New York standards, it’s a large apartment. [Laughs.] I love it. I go for long walks through the Roanoke area and Coleman Highlands. The whole area is very pretty.

Has your research influenced what the interior of your apartment looks like?

No. I can’t afford what I would really like, so it’s just very me. There’re tons of books. There’s some decent furniture. I like that my friends say my apartment looks like me.

When you are inside the grand houses you love, do you imagine what it would be like to live in them? Is it hard to have such a deep appreciation for them and not be able to afford to live in one?

When I was younger, I certainly did fantasize about living in many of the houses that I’ve written about. But as I have matured, I simply analyze the exterior and interior elements to create a framework for my writing.

The houses in your books all exude character and personality. Why do you think that is often absent in large houses today?

The problem is, we don’t see our homes as homes anymore. We see them as investments. We’re going to flip them. I find that the upper classes are now emulating the upper middle class.

How so?

The furniture is all contemporary. It’s more expensive than Restoration Hardware modern, but it’s the same look. It used to be with the upper classes that you could see things in their homes that they picked up along the way in life and from their travels. You don’t see that anymore.

Another problem is when owners of older homes take down walls and you can see the kitchen sink from everywhere. It’s ridiculous. In Prairie Village taking a wall down between the living and dining room works very well, but why are you taking walls down in a big house with big rooms? It doesn’t make any sense.

But I’m hearing from my friends in the business that that trend is changing. People want walls again. They don’t want to live in an auditorium.

Do you have any other insider predictions about interior trends?

I think antique furniture will come back. My theory is that there was the Great Depression and then World War II and after that, everyone wanted modern. Now we’re in another phase that started in the 1990s where everyone wants modern. But I think the pendulum will swing back because it looks so soulless. Not just here. The homes in those pencil towers in New York, for example, look like luxury hotel lobbies. There’s nothing you could associate with a human being in them. I think that is going to end.

There’s an apartment in New York at 820 Fifth Avenue that belonged to Jayne Wrightsman of the Wrightsman Galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She died a few years ago and her apartment on the third floor is a half-block long facing Central Park. They can’t sell it. My theory is that Wrightsman was known for impeccable taste, and the inside is full of boiseries and beautiful detailing, and that isn’t the style now, but no one wants to be known as the person that ripped that out.

But history tells us things will change. People will get tired of the coldness of a really contemporary interior. At auction, museum-quality antiques are still demanding high, high prices.

I loved the stories in Kansas City Houses about the owners of the homes. Why did they interest you? Why not just write about the architecture?

Because that’s not what I wanted to read. The books are about documenting structures, so I want a floor plan, I want photos, and I want to tell the story of who commissioned the house. It fascinates me, people who have the wherewithal to build whatever they want, what do they choose to build? Plus, these people were the movers and shakers of their day, so they were important to the growth of the community. They’re just interesting people who did interesting things.

Are you working on another project?

There’s another book that we need to find funding for. Prior to 2008, publishers would take risks on niche audience books. Now, not so much. You have to find funding for them. The book is on the houses of Ogden Codman Jr. You won’t know who he is, I’m sure. . .

You are correct.

But you know Edith Wharton, right? Her first book, which was not a novel, was called The Decoration of Houses. She co-wrote it with Ogden Codman Jr. It is a treatise on moving away from Victorian clutter to more classical simplicity. So [Wharton and Codman] helped move that European Revival style to the forefront. When you go into a luxury hotel in Paris and it’s that Louis XV, Louis XVI style, very simple, that’s what they espoused.

Codman did a lot of interior decoration, but he also built 22 houses completely from scratch. Edith Wharton is the one who introduced him into Newport. Since you lived in Newport. . .

In Navy housing, yes.

You know the Breakers. On the second floor of the Breakers, the rooms are quite a bit different from the grand rooms downstairs. The rooms upstairs are a little simpler, so elegant. Ogden Codman designed the rooms upstairs. Then that introduced him into the deeper pockets of the New York socialites, and that’s how he got established.

I’m working on another project with a gentleman here in Kansas City named Bill Bruning. We’re working on a book on New York penthouses and maisonettes. Do you know what a maisonette is?

In France, it’s an apartment on two floors.

In New York it’s a little different. Let’s say you have a Park Avenue apartment—a maisonette has an exterior door, so you don’t have to go into the lobby. It can be a single floor to three floors. Bill has an amazing collection of New York City floorplans. He’s been collecting them for decades.

Then there’s another book we need to find funding for. It documents Kansas City stores. That’s already written. It’s about all the great Kansas City stores over the years—Woolf Brothers, Emery Bird Thayer, Swanson’s, Harzfeld’s, Halls, Mindlin’s, Adler’s, Chasnoff’s, Cricket West. They were gorgeous. And the stories about the people that owned them are fascinating.

Share one quick one.

Kansas City had a Kentucky Derby winning horse, Lawrin, in 1938. It was owned by Herbert Woolf of Woolf Brothers, and it was raised at 83rd Street and Mission Road, where Woolford Farm was.

Interview condensed and minimally edited for clarity.